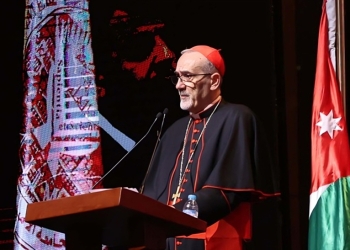

Peace, the profound yearning of human beings throughout the ages

12 November 2025, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

Introduction

First, I would like to thank you for your invitation. It is an honor and a joy to speak at your esteemed Bulgarian Academy of Sciences in Sofia on this centenary of the appointment of Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, the future St. John XXIII, as Apostolic Visitor here in Bulgaria. The so-called "Bulgarian Pope" is an icon of the deep desire that every generation, in every age and culture, has felt– often amid war – for a horizon of peace.

As you know, in 1925, my fellow countryman (born just 27 kilometers from my native village) was appointed Apostolic Visitor to Bulgaria, beginning his diplomatic career. He remained until 1934. After his episcopal ordination, he left to assist the small Catholic communities of the Latin and Eastern rites. He worked in a challenging context marked by poverty, religious tensions, and political instability. He dedicated himself to reorganizing the Catholic Church, improving relations with the government and the royal family, establishing contacts with the Orthodox Church, and supporting the poor by founding the "Pope's Refectories" for refugee children. In particular, in his relationship with our beloved Orthodox brothers, Monsignor Roncalli managed to set aside the little that divides us, focusing instead on the much that unites us. The assignment, initially temporary, lasted ten years and led to the creation of the Apostolic Delegation, of which Roncalli became the first representative in 1931. In 1933, he reported to the Bulgarian Prime Minister:

You know that I have behind me neither cannons, nor commercial treaties, nor political or financial interests against Bulgaria, but I am a humble servant of the most peaceful sovereign in the world, who is nevertheless the repository of a doctrine and a discipline that are worth more than any material power and are unbreakable. No one can doubt that I speak to you with sincere love for Bulgaria.

Among the many aspects of his work, St. John XXIII left an indelible mark on history for his firm determination to convene and inaugurate the Second Vatican Council. The enormous scope of his legacy is intimately connected with the renewal of the Council, which also embraces the dimension of peace. For John XXIII, the Council and the promotion of peace were closely intertwined: by renewing its image, the Church opened itself to the world with the intention of overcoming barriers and conflicts, leading the Church toward new horizons while remaining fully faithful to the deposit of faith.

The theme you have chosen for my contribution is taken from the opening sentence of Pacem in Terris, the Pope's Encyclical Letter "on peace among all peoples, founded on truth, justice, love, and freedom." This is our yearning, in the Holy Land and in the world; this is what we desire with renewed ardor in this Third Millennium.

1. An enlightened ambassador of peace amid the dark clouds of war

Roncalli was elected Pope in 1958, during a period suspended between two conflicts: World War II, still vivid in collective memory, and the Cold War, which threatened rearmament and destruction in the name of balance. In this context, he chose to speak of peace not as a slogan, but as a possible and necessary undertaking.

In 1961, the Berlin Wall was erected. In October 1962, just five days after the inauguration of the Second Vatican Council, the world stood on the brink of global nuclear war due to the Cuban missile crisis. At the height of this crisis, Pope Roncalli delivered his most famous and heartfelt warning to those responsible:

As the Second Vatican Council opens, amid the joy and hope of all people of good will, threatening clouds once again darken the international horizon and sow fear in millions of families (...).

In this regard, we remind those who hold positions of power of their grave responsibilities. And we add: with their hand on their conscience, may they hear the anguished cry that rises to heaven from every corner of the earth, from innocent children to the elderly, from individuals to communities: peace! Peace!

Today we renew this solemn plea. We implore all those in power not to remain deaf to this cry of humanity. May they do everything in their power to save peace. In this way, they will spare the world the horrors of war, whose terrible consequences cannot be predicted.

May they continue to negotiate, because this loyal and open attitude is a great testimony to the conscience of each person and before history (Radio message, October 25, 1962).

We tend to forget that the nightmare of war was averted thanks to the intervention of St. John XXIII, who noted in his diary on November 20: "Received the Polish Ierzy Zawieyski, confidant of Cardinal Wyszyński and well accepted by Mr. Gomulka, who asked him to convey his greetings to the Pope and to tell him that he considers the resolution of the terrible Cuban affair to be due to the Pope himself."

This, then, is the dramatic context that prompted St. John XXIII to write the encyclical Pacem in Terris, expressing his longing for peace. The doctrinal lines outlined in the encyclical "arise or are suggested by requirements inherent in human nature itself, and fall, for the most part, within the sphere of natural law" (n. 82). It should never be forgotten that, for Christians, what is divine and authentically Christian is also genuinely human, and vice versa. Christianity, therefore, can and must dialogue with every person of every age, assuming an irreplaceable role in building a new civilization of love, while remaining aware that it can never establish the kingdom of God on this earth in an absolute manner.

In the general audience of April 24, 1963, the "Pope of Peace"– as he was called– paraphrasing his famous speech to the Moon (October 11, 1962), addressed those present, inviting them to be itinerants of peace:

Returning to your homeland, to your home, be bearers of peace everywhere: peace with God in the sanctuary of conscience, peace in the family, peace in your profession, and peace with all people, as far as it depends on you. In this way, you will be assured of the esteem and gratitude of all, and the favor of Heaven and earth. Always be travelers of peace.

The encyclical Pacem in Terris remains one of the most lofty and courageous texts of twentieth-century moral diplomacy. For the first time, a pontiff addressed not only Catholics but "all men of good will," recognizing that peace is a universal, non-denominational right, a good that precedes and transcends differences in faith, ideology, and culture.

It is no coincidence that St. John XXIII chose to promulgate Pacem in Terris in 1963, one year after the opening of the Second Vatican Council (October 11, 1962), which he inaugurated with words that still resonate today for their depth and vision:

After almost twenty centuries, the situations and grave problems facing humanity remain unchanged; in fact, Christ still occupies the central place in history and life: people either adhere to him and his Church, and thus enjoy light, goodness, right order, and the good of peace; or they live without him or fight against him and remain deliberately outside the Church, and for this reason there is confusion among them, mutual relations become difficult, and the danger of bloody wars looms.

On the other hand, in Pacem in Terris (No. 5), St. John XXIII sought dialogue even with non-believers, that is, with all people of good will, when he declared that the foundation of peace is "the principle that every human being is a person, that is, a nature endowed with intelligence and free will; and therefore is subject to rights and duties that spring immediately and simultaneously from his very nature: rights and duties that are therefore universal, inviolable, inalienable."

Pope Roncalli died less than two months after the promulgation of Pacem in Terris, which therefore constitutes his spiritual testament. Two weeks after the Pope's death, President Ho Chi Minh, convening the Central Committee of the North Vietnamese Communist Party, prepared North Vietnam for war with the United States, uttering words that are as prophetic as they are relevant in light of recent conflicts: "The war that is coming will be tough (...), I may lose a thousand men for every American soldier who falls, but the outcome will still be what I expect, because we will win the war and the United States will lose it." The dramatic assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy in Dallas a few months later paved the way for the disastrous US intervention in Vietnam and thus the failure of peace.

2. Peace, the deep longing of every human being

What does it mean to say that peace is a "deep longing of human beings of all times"? "Longing" comes from the Latin anhelitus, meaning "labored breathing," a desire that becomes almost painful. Peace, therefore, is not only the absence of war, but a suspended breath – a constant tension toward something that seems to elude us, yet we continue to seek it.

From the dawn of humanity to the present day, peace has never ceased to be mentioned, invoked, promised, betrayed, and invoked again. It is the dream of humanity, which has known the fragility of flesh and the ferocity of power, yet refuses to resign itself to the logic of violence.

John XXIII was not a naive idealist. He was a child of war. He served as a military chaplain during the First World War and experienced the tensions of the Second World War as a diplomat in Bulgaria, and later in Turkey, Greece, and France. He knew that peace is not built with slogans, but with the patience of daily gestures. In his view, peace is not an abstract utopia, but a reality that requires justice among nations, respect for human rights, integral human development, dialogue between religions, institutional responsibility, and free consciences. In this, he spoke as a man, not only as a diplomat or Pope. He was well aware that many nations were moving in the opposite direction, as we can sadly see today. Pope Roncalli nevertheless wanted to help the Church, as it set out to rediscover its identity in the Second Vatican Council, to read with hope the history of the world in which it was situated, to create a common basis for dialogue with all people, and to proclaim to the world that peace is not impossible, that it should not be considered a utopia.

Today, we are called to raise the same cry in the same desert: we live in an increasingly technologically advanced world, but one that is often spiritually and morally exhausted. The war is not over. It has only changed form: hybrid wars, economic conflicts, digital colonialism, military and political violence disguised as cultural identities and religious crusades, and more. Peace, therefore, remains a yearning, but also a challenge that is more relevant than ever.

After all, speaking of the yearning for peace– in today's world, so marked by wars, fears, and polarization– is an act of cultural and spiritual resistance. It affirms that humanity is not destined for conflict, but possesses a greater force within: the ability to create bonds, to heal wounds, to imagine a different future. Peace is not just a goal; it is a journey to be undertaken together, a daily choice, and the highest expression of human dignity. There will never be peace in the world until there is peace in the human heart.

The peace that the Church is called to invoke and build is universal shalom, the gift of Christ in the Upper Room. The Hebrew concept of shalom encompasses fullness, order, and harmony, in perfect accord with the opening words of Pacem in Terris ("Peace on earth, the deep longing of human beings of all times, can only be established and consolidated in full respect for the order established by God," n. 1) and consistently reiterated throughout its text. Peace is not merely the suppression of differences or minorities, nor simply a non-aggression pact; it is an authentic and cordial acceptance of the other, a "stubborn" willingness, so to speak, to listen and dialogue. It is an open path, where fear and suspicion give way to knowledge, encounter, and trust, and where differences become a source of companionship and collaboration, rather than a pretext for conflict.

Peace is not only a divine reality but also a human and social one – a universal value and an imperative duty that calls everyone to respond, under penalty of humanity’s self-destruction. However, even in the anthropological sense, peace is not limited to mere social convention, armistice, truce, or absence of conflict, nor is it simply the result of diplomatic efforts or delicate geopolitical balances– balances that are increasingly unstable today. Of course, in such conditions, even this would already be a valuable achievement. Yet peace is much more than that: it is rooted in the truth of the human person, the sole founder of an authentic omnium rerum tranquillitas, according to the teaching of St. Augustine (De Civitate Dei XIX,13,1), because it is established in accordance with justice and charity.

To achieve this, it is necessary to bring God and humanity back to the center, to return to the face of the other, to the centrality of the human person and his irreplaceable dignity. Only within the integral development of the person, respectful of fundamental rights, can an authentic culture of peace take root and unarmed prophets, witnesses, and pillars of peace arise. Today more than ever, the world needs such figures, even at the cost of persecution, discredit, or being considered utopians and visionaries. For peace, it is always necessary to take risks. We must be ready to lose honor, even to offer our lives, as Jesus Christ did.

No one can consider themselves an island or live as a "monad" in today’s global village, which is now our common home: when we destroy the face of the other, our own also vanishes, especially in this era of profound global interconnection. If we sink, we sink in the same boat, because today more than ever we are part of a common and intertwined world. Therefore: forgiveness or shipwreck, communion or dispersion, peace or annihilation. In our encounter with others, the absolute, the essential, the future of humanity or its extinction is at stake.

For us believers, the Lord Jesus, entering the world, did not evade or minimize the drama of humanity and history, but took it fully upon himself, carrying it on his shoulders as the true Lamb of God who takes upon himself the sin of the world. In the face of violence and death, he did not surrender passively but gave himself up, manifesting a love greater than all evil. In the anguished night of Gethsemane, neither sleep (Mt 26:40), nor the sword (Mt 26:52), nor flight (Mt 26:56) was his response; it was the total gift of himself until the end.

It is the Lord himself who warns us: “Put your sword back in its place, for all who take the sword will perish by the sword” (Mt 26:52). This teaching applies to each of us in our personal, family, ecclesial, social, and political lives. How many sword blows are inflicted on one another, even within our Church! The new, the other, always intimidate us, and so we instinctively perceive them as enemies: homo homini lupus.

And here is the only way to true reconciliation: to confess that we too, in our own way, are not only victims but also potentially perpetrators; to recognize that the violence we see outside ourselves is not as distant as we would like; to consider that the wounds of others are not foreign to us but affect us in body and spirit; to admit, finally, that we all need healing. Only in this way can we perceive in others a res sacra – as Seneca said – and, as believers, Christ himself, since for a Christian, the other is Christ: homo homini Christus.

3. The tragic failure of peace

Throughout history, countless times, humanity and even God himself have had to acknowledge the failure of peace. This is also the dramatic experience of the person praying in Psalm 120:7: אֲנִי שָׁלוֹם וְכִי אֲדַבֵּר הֵמָּה לַמִּלְחָמָה, which literally in Hebrew can be rendered: "I am peace, but when I speak of it, they are for war." It is a verse of great poetic and spiritual power: it expresses the loneliness of those who desire peace in a world dominated by violence and misunderstanding.

The words of the prophets also bear witness to the dramatic failure of peace. As Jeremiah states, lies and deceit are rampant, while "Peace, peace!" is proclaimed in vain, and there is no peace (Jer 6:14; 8:11). It is the loneliness of the prophet, the anguish of those who helplessly witness the triumph of injustice, to the point of crying out to God himself, who seems to remain silent in the face of evil, as Habakkuk laments when speaking to the Lord: "How long, Lord, must I call for help, but you do not listen? I cry out to you, 'Violence!' but you do not save" (Hab 1:2). Yet even this cry, this anguish in the face of the violence and sin of the world, is already the word of God: it is divine sorrow reflected in the heart of man.

Is it still possible to think of peace today in the Holy Land? The very term "peace" seems to have been emptied of meaning: a distant, almost utopian word, often bent to interests and manipulations. Even those who invoke it sometimes declare it unattainable except through war– a contradiction that betrays their despair.

Our land continues to bleed; our people live in fear and uncertainty. Too many around us see only ruins. Yet it is precisely from these ruins that the hope of peace can and must be reborn – not as an illusion, but as an act of stubborn faith, as resistance of the heart that refuses to give in to hatred.

The failure of peace is always a defeat, because war, even if sometimes necessary or legitimate as a last resort of defense, is never "just" in the true sense of the word. In his choices, man can at best seek the least unjust remedy for evil, but war always remains a scourge, because "blood calls for blood." Even so-called defensive war can prove morally unjust if it exceeds the bounds of reason and justice, just as defense is not always legitimate.

Added to this moral defeat today is that of the institutions called to safeguard peace: international organizations, once a bastion of hope, now appear weak and lost.

In the Holy Land, the drama of the failure of peace is unfolding – a tragic stalemate in which Israelis and Palestinians have imprisoned each other. Israel fought a war of retaliation led by a leader lacking popular support; Gaza, holding hostages, watched helplessly as its own people were destroyed. Both seem to have chosen the desperate path of Samson: "Let me die with the Philistines!" But today it is not a single hero at stake, but entire nations.

Moral reasons are confused: each claims God as its ally, turning faith into an instrument of justification and hatred. When religion bows to the logic of violence, all that remains is external intervention capable of probing the root causes of failure and pointing to a path of reconciliation that will take generations. The wounds, in Israel as in Palestine, are deep; the local Church itself is in danger of disappearing, suffocated by the fear and despair of the few faithful who remain.

It is not enough to stop the weapons; a vision for the future is needed, one that has so far been denied by the blindness of leaders and extremist fringes on both sides. Armed coexistence cannot last: without a plan for peace, mutual destruction is inevitable. The international community must isolate the forces that thrive on war– economic, political, and ideological– because as long as they dominate, the righteous and the innocent are left alone. The Holy Land is not only a strategic hub in the Middle East, but the symbolic heart of the world: when it is on fire, the whole world burns.

4. New aspirations and horizons for peace beyond failure

Genuine peace takes time. It should not be confused with the mere cessation of hostilities: the end of war does not coincide with the end of conflict, nor does it automatically mark the beginning of peace. It is only the first step, made possible by hope that springs from faith. Only a trusting soul can help make what it believes in a reality.

New leadership is needed– both political and religious– capable of generating a different language based on mutual respect and the dignity of every person. The wounds are deep, and the road will be long, but the hope for lasting peace must remain alive, sustained by the shared will to believe in it and to patiently prepare the conditions for it to mature.

This generation has the task of laying the foundations for the freedom of the next, gradually creating a culture of respect and dialogue. After terrible years, it is hoped that the new phase will truly mark the end of a nightmare, not just a brief respite. Despite their diversity of opinions and perspectives, Israelis and Palestinians today share a deep desire to return to life, not as before, but in a new way, free from the logic of violence.

Until now, each side has been closed in its own pain, unable to accept that of the other. The hatred sown over time, rooted in narratives of contempt and exclusion, requires a renewal of language and witnesses. New words need new faces capable of embodying them.

In the West Bank, the situation remains fragile and deteriorated: isolated communities, freedom of movement hampered by hundreds of checkpoints, and the absence of an authority that guarantees security and justice. The economy is also suffering: cross-border work and pilgrimages, the main sources of livelihood, are suspended, aggravating the precariousness of families, especially Christian ones. The local Church, though small, plays an essential role: it invites us to look beyond the Palestinian question alone, recognizing the pain and complexity that also exist in Israeli society.

To remedy the failure of peace, it is necessary, now more than ever, to re-establish a true culture of peace, capable of permeating every level of human and social life. In a time torn apart by conflict, the Church is called to be a sign and instrument of possible peace – not so much through political power or diplomacy, but through the building of reconciled, welcoming, and fraternal communities, places of encounter and authentic dialogue. We can never be credible peacemakers if we remain divided or hostile within ourselves: the unity of the Churches cannot be reduced to superficial ecumenism, but must be embodied in concrete gestures of communion.

In the Middle East, where religious and cultural diversity is part of daily life, churches are called to counter the logic of confrontation with the art of dialogue and encounter – not out of calculation or convenience, but because dialogue is intrinsic to the relationship between God and humanity. Ecumenical and interreligious dialogue, now more than ever, must be renewed. It is necessary to face honestly what has happened – both spoken and unspoken words – not to remain prisoners of the past, but to overcome it with awareness. Difficulties abound, but our common duty is to help communities look ahead with confidence and serenity toward a different future.

This war marks a turning point in interreligious dialogue, which, between Christians, Muslims, and Jews, can no longer continue as before. The Jewish community has perceived a lack of support from Christians; Christians themselves have appeared divided or uncertain; and Muslims feel attacked and suspected of colluding with violence. After years of dialogue, we now face profound misunderstandings, which bring both pain and valuable lessons. We must begin again from this experience, aware that religions play a central role in guiding coexistence and that dialogue must address differences, wounds, and local sensitivities, no longer limiting itself to Western perspectives. The path will be more difficult, but it is necessary – not out of obligation, but out of love.

When sincere and rooted in the reality of communities, interreligious dialogue fosters a mindset of encounter and mutual respect, creating the essential foundation on which to build future prospects for peace and political collaboration.

Being a believer does not mean closing oneself off in defense of personal certainties, but having the courage to confront them with others, recognizing that faith is manifested in relationships. Interreligious and intercultural dialogue thus becomes the main road for responding to the challenges of the present. In regions where religion structures society, dialogue between faiths is not an academic exercise but a vital necessity, capable of influencing civil relations and even laws. However, it cannot remain confined to the upper echelons of religious authority; it must reach the people, becoming part of the daily fabric of fraternity. Interreligious dialogue is, ultimately, a pilgrimage: an exodus from oneself to encounter the other, allowing oneself to be challenged to responsibility and shared growth. It is a path of mutual knowledge and trust, an alliance of hopes that alone can lead humanity toward that peace which no one can build alone.

The Mother Church of Jerusalem has a unique vocation at the heart of the one Church of Christ: to bear witness that it is possible to build relationships of peace even where conflict, tension, and division prevail, and where speaking of hope seems futile. Sent to proclaim the Gospel of justice and peace through word and deed, it is called to be a sign of a “different” world, founded not on force but on truth and mercy.

This mission, however, often places it at a crossroads: on one hand, the urgency of denouncing the violence and injustice that crush the weakest; on the other, the risk of reducing the Church to a political entity, losing sight of its prophetic and spiritual nature. The Church must exercise parrhesia, the evangelical courage to pronounce judgment on the world according to the Gospel, without falling into the logic of confrontation or factionalism. This does not turn the Church into a political party, but commits it to being the voice of those who have no voice, to denouncing injustice without condemning people. Its mission is not to oppose, but to serve; not to accuse, but to heal. Even when it is silent, it does so to preserve the truth in the meekness of Christ, the Lamb who did not respond to hatred with hatred, but overcame evil with good.

Thus, while sharing with civil authorities the responsibility for the common good, the Church does not adopt a logic of competition and power. She loves and serves the polis, always defending the rights of God and humanity, and remains faithful to her only possible position: that of Christ, at the service of the life of all.

Rebuilding peace means, above all, educating for peace at every level, starting from childhood. When ideology takes precedence over the person and the other is seen as an enemy to be eliminated, peace is already lost. Building peace is therefore both a collective and an interior task, requiring the conversion of each person: we are all called to become artisans of peace.

The antidote to violence is to create hope, spread it, and educate people about hope and peace. Schools and universities have a decisive role: there, the culture of encounter and nonviolence must be renewed, based on knowledge and mutual respect – an urgent task in the Holy Land, where Jews and Arabs often grow up separated. Being prophets of peace means looking with compassion at the pain of both peoples, loving them together, and feeling them both as brothers and sisters. Only in this way will walls fall and bridges of authentic fraternity arise, capable of a love that overcomes every barrier.

There is a Christian way of living in the Middle East, even in times of war. Jesus was neither an armed revolutionary nor an ideologue of violence; his revolution is that of love, which transforms the world without worldliness, giving time a taste of eternity and history a divine meaning. In him, peace is not a utopia but a concrete path of redemption for humanity.

It should not be forgotten that after the most devastating experience in biblical history– exile– the prophets of Israel were able to give voice to hope once again. Among their words, Haggai's exhortation resounds with force: "Take courage, all you people of the land," says the Lord, "and work, for I am with you" (Hag 2:4). The prophet encourages a people who are lost, convinced they cannot rise from their ruins. It is the same despair that sometimes assails us today, when everything seems lost. Yet the prophet calls on the leaders and the people to rebuild the house of the Lord and the ruined city. Today, in the Holy Land, throughout the world, and in the Church itself, we are called to a similar task: to rebuild what has collapsed, to heal the fractures of unity, to restore beauty and harmony, and to become architects of peace.

But peace cannot be built by ignoring wounds. A peace that is merely the “absence of war” is fragile and deceptive. Some wounds remain forever etched in the bodies and souls of peoples: they cannot be erased, but they can be transformed. Those who care for human frailty know this well: we are all called to become “wounded healers,” capable of turning pain into compassion and service. It is not enough to understand the causes of trauma or conflict; we must confront them and convert them into healing power. This is the path of the disciples of Emmaus (Lk 24:17): they flee from Jerusalem with darkened faces, wounded and disappointed, but they encounter the wounded Healer, the risen Christ, who heals them with his own wounds (cf. Is 53:5; 1 Pt 2:24). In him, they understand their own wounds and find the path of hope, returning to the Holy City. In this way, our personal, social, and ecclesial wounds can also become instruments of salvation, opportunities to understand and heal the wounds of others.

There can be no true peace without the possibility of forgiveness and reconciliation. Peace is not an abstract concept or a simple act, but a way of life, an integral attitude of the person and the community, which must confront the wounds of the past, sin, and hatred. In this sense, peace and forgiveness are closely linked: one cannot exist without the other. The Bible teaches that forgiveness has its roots in God's love and requires a personal journey of understanding and accepting the evil suffered or committed. It is not a matter of forgetting, but of consciously facing the wrong, overcoming it, and directing it toward a greater good. Only in this way does forgiveness heal wounds, change hearts, and produce peace.

At the social and political level, forgiveness requires a long time and a complex journey: collective wounds, different perceptions of pain, and shared historical memories must be taken into account. Until there is mutual recognition of the evil suffered and committed, wounded memory will continue to weigh on future relationships. Faith opens us to relationships, to encountering God and others, but cultural and human formation is also necessary to teach us to view events with a broad perspective, oriented toward the common good and the future.

The first fruit of forgiveness is liberation from resentment and revenge, which imprison the soul and block all relationships. It allows for inner healing, reactivates life, and opens the future. We need to act at all levels of society– political, religious, educational, and media– so that forgiveness can fully affect every dimension of the human being.

The Church, together with other faith communities, plays a central role in educating people about reconciliation, but it cannot impose forgiveness: it is necessary to respect the time needed to grieve, helping people reinterpret history so that wounds can be transformed into instruments of healing. In the Holy Land, it is often necessary to know how to wait, patiently proposing the Christian path to peace.

The political agreements that have failed so far have shown that peace imposed from above, without considering wounds, pain, and the cultural and religious context, is doomed to fail. Therefore, it is urgent to propose concrete paths of forgiveness and reconciliation, to build relationships, to foster trust within the community and with other religions, and to accompany healing with inclusive language and gestures of life. Only in this way can peace become real and lasting, not just a slogan.

However, forgiveness alone cannot build peace, just as truth and justice without forgiveness cannot generate it. The relationship among these three elements is complex, often a source of heated debate, but also of profound reflection.

To speak of forgiveness without truth and justice is to ignore the dignity of man, created in the image of God, and to deny his right to a just and dignified life. Conversely, to demand truth and justice without a desire for forgiveness condemns the adversary to guilt without offering a way out, turning responsibilities into mere recrimination and fueling further conflict.

The Church's pastoral ministry must be able to sustain a continuous and diligent dialogue among forgiveness, truth, and justice, recognizing pain and respecting the rights of both God and humanity. Only in this way, gradually and in times that are not our own, can real prospects for peace be created. What sustains and unites all this is not an ideology, but the love of God, poured into our hearts by the Holy Spirit (Rom 5:5). This love is the soul of our longing for peace.

Today more than ever, the yearning for peace depends on education in hope: in respect, encounter, dialogue, and forgiveness. Jews, Muslims, and Christians are called to be credible witnesses of hope, rooted in the certainty of God's goodness toward all. Without hope, one cannot live, and today, unfortunately, there is more fear than hope. But fear is overcome with faith and hope.

Yes, this is the time for hope. The antidote to violence and despair is to create hope, to spread it, to generate it. We have a decisive mission: to educate for peace and nonviolence, to teach people to know and respect each other, to truly encounter one another – something that, unfortunately, still rarely happens among the younger generations, both Jewish and Arab.

Being prophets of peace means keeping our gaze fixed on the suffering of both peoples, Israeli and Palestinian, learning to love them together, to feel them both as neighbors and friends. Only in this way will walls fall and bridges of brotherhood be built, capable of a love that overcomes barriers.

As Pius XII said, "Empires not founded on justice are not blessed by God. Politics emancipated from morality betrays those who want it that way. The danger is imminent, but there is still time. Nothing is lost with peace. Everything can be lost with war. Let men return to understanding each other. Let them resume negotiations" (A.A.S., 1939, p. 334). Faced with the complexity of the world, global powers, and strategies, we may feel lost and powerless. Yet all is not lost, and we can still do much: every gesture of reconciliation, every word of truth, every act of faith in the future is a seed of peace that prepares the way for the repair and redemption of the world.